“Are You Lonesome Tonight?”

The song, originally written in the 1920s and famously sung by Elvis Presley in 1960, touches on a theme that has accompanied humanity since our earliest days. Some people cope with loneliness better than others. I know someone who lived like a hermit for most of his life and made it past 100. Others crave constant attention and social interaction—they can’t stand to be alone.

A few weeks ago, I visited Japan and had the opportunity to interact with many locals. Japan, as you may know, is a very ethnocentric country. Aside from tourists, it’s rare to meet residents who aren’t ethnically Japanese. Most people are friendly, smile often, and offer the traditional bow. I used to think that was just a Hollywood stereotype—but it’s very much real.

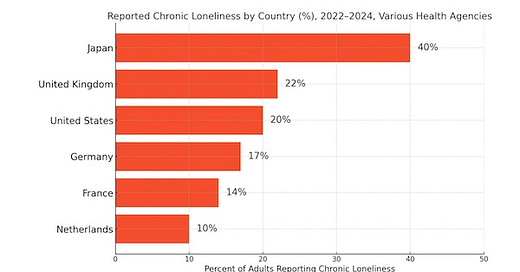

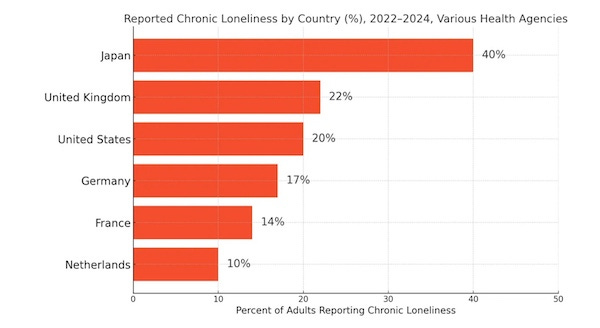

However, there’s something else happening in Japan that doesn’t receive much attention from the outside world: loneliness. According to various surveys conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Japan ranks among the top countries struggling with this issue.

The outward appearance of cheerfulness often masks inner sadness. We’ve heard this paradox before—how comedians often use humor to hide deep depression.

Despite Japan’s collectivist cultural roots that historically emphasized family, community, and interdependence, loneliness has become a deeply entrenched social problem. Psychologically, this paradox is rooted in the growing disconnect between traditional cultural values and modern life. While Japanese society once championed conformity, harmony, and group identity—values that helped build strong social ties—recent decades have seen rapid technological advancement, economic change, and shifting demographics disrupt these traditional frameworks. Young adults, for instance, are increasingly avoiding marriage as women pursue careers free from the expectations of domestic life.

Technology plays a complex, dual role in this trend. Japan is one of the most technologically advanced nations in the world, with widespread access to digital communication, automation, and robotics. On one hand, social media, online gaming, and virtual communities offer new forms of connection. But these interactions are often superficial and lack the emotional depth needed to satisfy human connection.

Young people often voluntarily withdraw from society and remain isolated for months or even years, relying primarily on the internet for interaction. While technology provides an escape from social pressures, it can also deepen isolation when it replaces genuine, in-person connection.

The elderly face another set of challenges. Many live alone in rural areas as younger generations migrate to urban centers. Technology is less accessible for them, and family networks are thinning. Japn has brought in robots to help alleviate loneliness. However, can an artificial companionship truly meet the human need for connection? Or does it risk fostering more emotional detachment?

Japan’s situation reveals how technology can both ease and worsen loneliness, depending on how it is integrated into daily life. Humans don’t just need communication—we need meaningful relationships, empathy, and belonging. When technology replaces rather than enhances those needs, it not only fuels loneliness but reshapes our understanding of what it means to connect.

And this issue isn't unique to Japan. The United States ranks third on the OECD’s loneliness index. Despite being the wealthiest nation on Earth, with unparalleled access to goods and comfort, many Americans report frequent feelings of isolation. So what happened to the promise of connection that social media—Facebook, Instagram, and others—once offered?

Much of today’s loneliness stems from the very technology we thought would bring us together. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the problem. Lockdowns cut people off from loved ones, particularly the elderly, who often couldn't even be visited during serious illness. Meanwhile, working from home, once a temporary solution, has become permanent for many—replacing vibrant office environments with solitary days in front of screens.

The consequences go beyond psychological well-being. Loneliness is linked to a host of negative health outcomes and rising healthcare costs. In the elderly, it increases the risk of dementia and mortality, particularly when paired with chronic illness. Among younger populations, it’s associated with psychological distress, substance abuse, and escalating mental health costs.

So what can we do about it?

Here are three simple, practical steps to reduce loneliness:

1. Reach Out to Someone You Know

Call—don’t just text—a friend, family member, or colleague. Even a brief check-in can help build connection. Consider inviting them for coffee or lunch.

2. Join a Group or Activity

Participate in a local club, hobby group, fitness class, or volunteer program. Shared interests naturally lead to conversation and friendships.

3. Get Outside and Be Around People

Visit a park, café, library, or community event. Even passive social exposure—being around others—can reduce feelings of isolation and lift your mood. After all, we are social beings by nature.

4. Devise a Daily Strategy

Write down a daily to do list that includes engaging with other people, even on a superficial level, to get away from technology.

Ok

$265 Rent? You might be wondering why rent is so cheap here. I can take you around our city of Otaru and show you literally hundreds of empty houses. The entire country now has more than 11,000,000 empty apartments and houses. The elderly population is dying off or going into:homes for the elderly or living with family now. The younger generation neither has the money nor the desire to live in their parent`s homes, even though some are really beautiful if fixed up. It is possible in southern Japan to buy a very large, what was once considered an upper middle class home, with land, for around $20,000 or less.That same house was probably around $150-200,000 when purchased.

When we first started working in

southern Japan in the city of Numazu, south of Tokyo, land was measured by 3 meters squared and sold for $1700 for that much land. The church was sitting on $255,000l worth of land and that was only about a quarter of an acre!. The country is expecting to diminish in population by about

one fourth of it`s current population by the year 2050, or 25 years from now. Young people do

not want to raise a family or have children; we are in an era of the the to "me" generation. They want nothing to do with any religion, anything that would cramp their "live now for me" style.

From a dear friend in Japan: